Year in Review

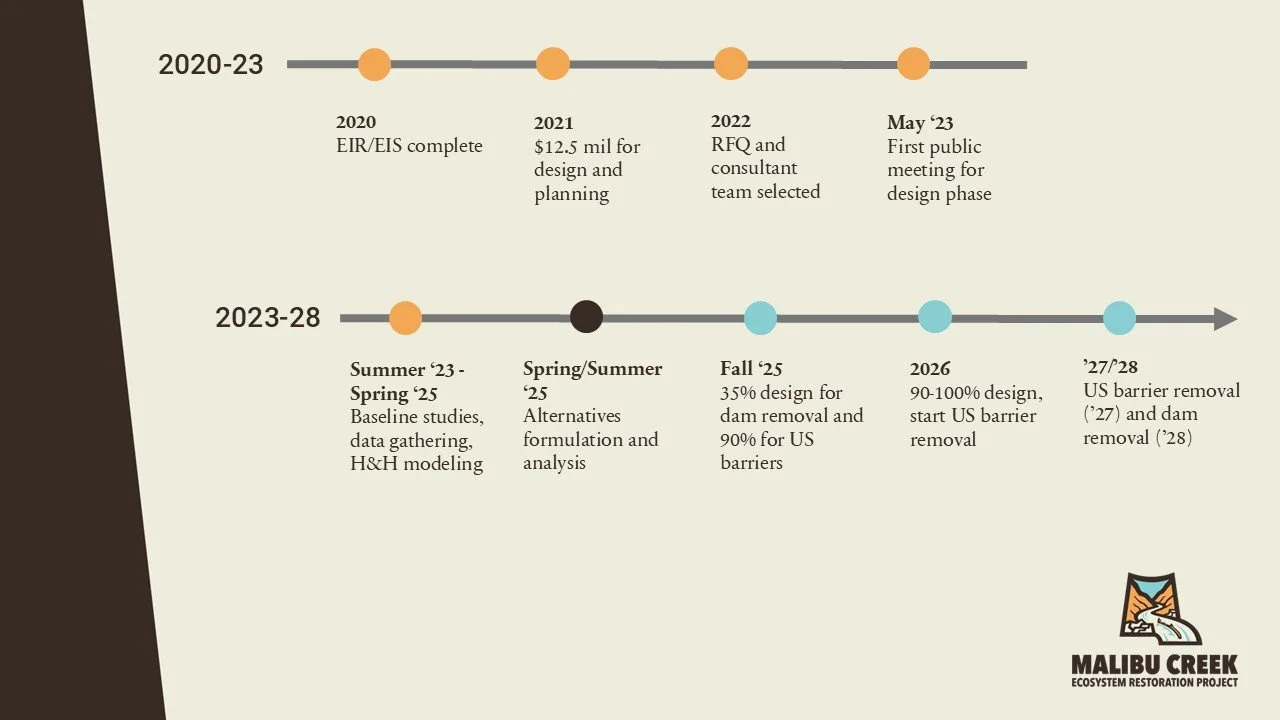

Project timeline

The Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project (MCERP) made major strides in 2025 toward restoring natural ecosystem functions and connectivity along Malibu Creek. The pre-construction, engineering, and design phase for removing Rindge Dam and addressing the upstream barriers advanced significantly, while public engagement remained central to building community support.

Highlights of 2025

Franklin Fire Recovery

Prior to the Palisades Fire, the Franklin Fire in December 2024 caused significant habitat damage in the lower part of Malibu Canyon south of Rindge Dam. The Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains stream team conducted a longitudinal habitat profile and cross section mapping along Malibu Creek to monitor post fire recovery. This data also assisted the MCERP project team with sediment transport modeling efforts.

By spring, native plants were bouncing back in the burn scar: black sage, toyon, wild cucumber, laurel sumac and sugarbush were among the sprouting species. While the mapping team saw no trout, invasive crayfish and carp have rebounded since the fire.

Modeling Best Methods for Removal

California State Parks and the project team further analyzed removal methods of the 100-foot tall dam and remediation methods of eight upstream barriers. Their findings determined that much of the trapped sediment behind the dam can be repurposed for beach nourishment or stored for future use, which helps build coastal resiliency and will also lower project costs.

Studies indicate that the trapped sediment behind the dam is good for nourishing local beaches.

“The removal of the dam will not only support habitat restoration and species recovery but also creates opportunities to reuse the sediment trapped behind the dam to nourish local beaches. This is sediment that would have naturally made its way to the coast if the dam had not blocked it. Additionally, by repurposing the material and avoiding landfill disposal, we anticipate significant cost savings for the project,” said R.J. Van Sant, project lead for State Parks.

Local partners, stakeholders, and local communities played an important role in the year’s progress. On August 20, 2025, a second public workshop was held to present hydraulic and sediment modeling results and a range of dam removal alternatives, along with a Surfrider Beach surf study, inviting the community to provide feedback and ask questions. These collaborations are invaluable and will help advance the project into the next design phase.

Community Science Program

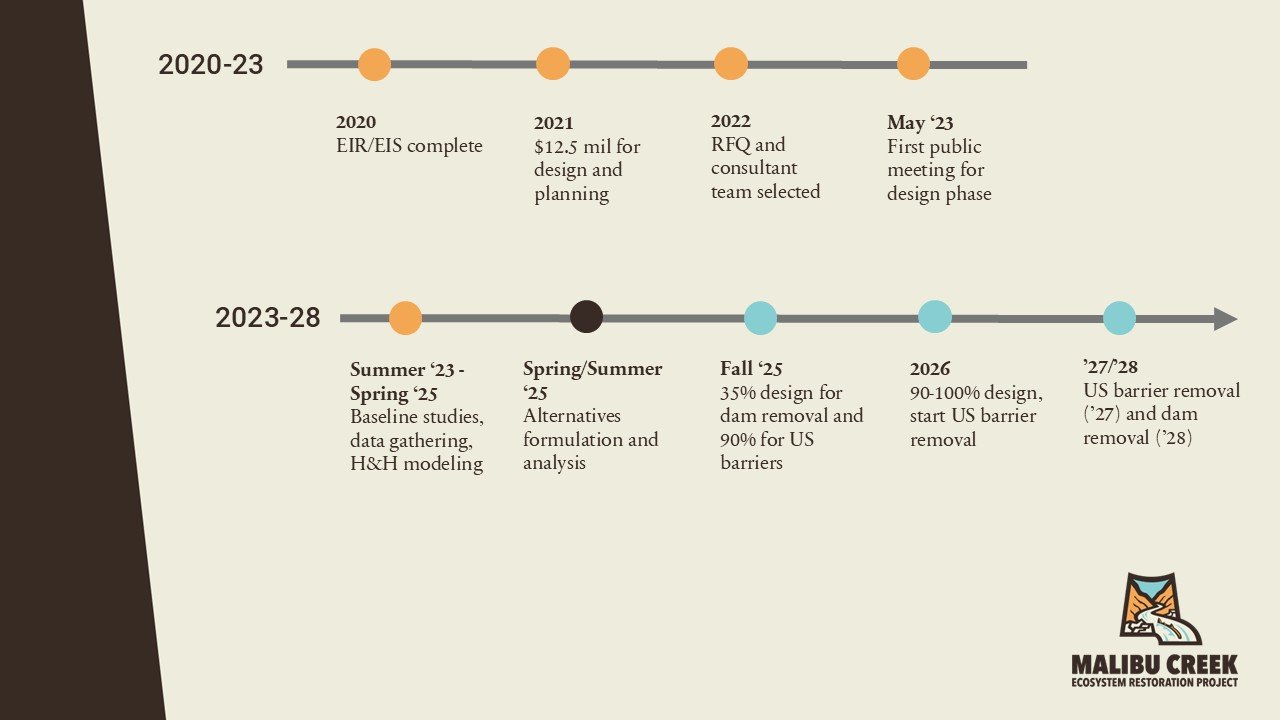

The Community Science Program continued to grow last year, offering the public a hands-on role in documenting the landmark restoration. With seven photo monitoring sites now active, volunteers helped us collect over 2,100 images—creating a visual record of Malibu Creek at a landscape scale.

Participation is simple, yet impactful--snap photos at the designated monitoring sites and upload them to our database to help track and document changing conditions along key areas of Malibu Creek.

Public Outreach and Education

Our public outreach continued to engage all ages across Los Angeles, from the LA County Fair to creek side at Malibu Creek State Park, discussing southern California steelhead recovery, wildlife corridors and ecosystem biodiversity. We also offered tours about species migration through the Malibu Creek watershed for groups to witness how aquatic connectivity is essential for species survival.

Interested in scheduling a tour or learning more about our outreach programs? Email us at restoremalibucreek@caltrout.org.

Sand’s Alive!

Sandy beaches aren’t just for dramatic sunsets. They’re dynamic ecosystems that connect land and sea, boosting coastal resilience, filtering water, providing food and serving as nurseries for plants, fish, reptiles, and birds.

Photo Courtesy of National Park Service

The Movers and Shakers of Sandy Beaches

Photo Credit: LiMPETS Program: limpets.org

Sandy beaches aren’t just great for dramatic sunsets. They’re dynamic ecosystems that connect land and sea, protecting against coastal erosion, filtering water, providing food and serving as nurseries for plants, fish, reptiles, and birds. They harbor a hidden biodiversity of both marine and terrestrial organisms.

Nutrient-rich kelp wrack (lower right) is part of the beaches’ ecosystem. Photo courtesy of State Parks.

Looking closely at the high tide line in piles of seaweed and debris (referred to as wrack), where damp sand meets saturated sand, you might find an array of crustaceans such as beach hoppers (amphipods), beetles, and blood worms. These macroinvertebrates scurry, hop, and crawl up and down the beach daily, following the tides. Upper beaches also host sand dwellers such as isopods (roly-polies being one example), burrowing from the high tide line up to older wrack piles.

The Hidden World Beneath Your Feet

The migrating long bill curlews en route to their wintering grounds along the coast rely on insects, marine crustaceans, and bottom-dwelling marine invertebrates found at the shoreline.

At the shoreline you’ll also find sand dwellers such as pacific mole crabs (aka sand fleas) and bean clams that dig into the saturated sand. Sand crabs often gather in feeding groups in the swash zone, where waves wash up and down and also where sediment transport and coastal processes take place. The tiny holes or V-shaped ripples in the sand you might see are caused by wave wash flowing over the crab’s antennae. Shaped like small eggs and growing up to 1.5-inch long, these critters spend their lives following the tides in order to remain shallowly buried. Digging into the sand backwards, they can bury themselves completely in less than 1.5 seconds. Unlike most crabs, they have no claws and eat plankton caught in their antennae.

A Vital, Overlooked Ecosystem

Sandy beaches are often overlooked as a vital and biodiverse ecosystem that serves as a bridge between marine and terrestrial environments. They harbor high densities of detritus, infauna, and macro-invertebrates, organisms providing food and habitat for both marine and terrestrial species. They also play a role as a bioindicator for monitoring healthy, functioning ecosystems. For example, when crabs eat plankton contaminated with neurotoxins, they become toxic to the birds, otters, and fish that eat them. Scientists use them to assess the health of marine ecosystems.

Sea gulls enjoying a dramatic sunset.

SCOUP: A Coastal Resilience Effort

California’s sandy beaches are more than just recreational spaces —they’re a cornerstone of our environment, economy, and quality of life in Los Angeles. Learn how SCOUP will help protect our coastlines against rising seas.

Photo Credit: Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors

Protecting California’s Beaches

California’s sandy beaches are more than just recreational spaces —they’re a cornerstone of our environment, economy, and quality of life in Los Angeles. They also serve as a refuge for inland communities during extreme heat, an escape that’s becoming more frequent as our climate changes.

According to Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors (LACDBH), in recent years sand is disappearing faster than new sediment is arriving. Beaches are shrinking and the roads, buildings, and public spaces along them are becoming vulnerable to rising seas.

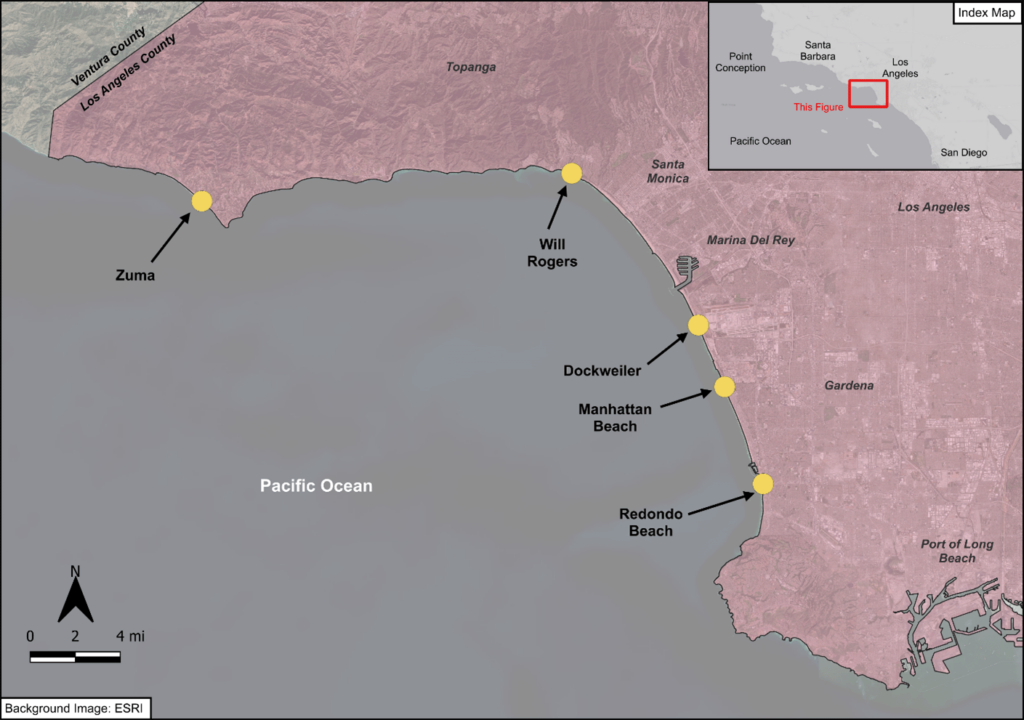

Popular beaches facing erosion risk in Santa Monica Bay.

LACDBH is turning to innovative strategies that address multiple environmental challenges while shoring up our diminishing beaches. Working with the County Board of Supervisors, the agency has launched the SCOUP (Sand Compatibility and Opportunistic Use Program). SCOUP will repurpose high-quality sand from sources like construction projects, dredging, and flood control maintenance; sand that might otherwise end up in landfills or industrial use, by placing that material on local beaches. The comprehensive coastal resilience strategy will help nourish local beaches by adding clean, compatible sand to combat erosion and prepare for rising sea levels.

Beach Sand Placement Locations

While much of our coastline is challenged by sea level rise, certain sites have been identified to receive SCOUP sediment due to their erosion risks, infrastructure, recreational value, and ecological considerations. The five beaches rolling out the program are:

Zuma Beach

Will Rogers State Beach

Dockweiler State Beach

Manhattan Beach

Redondo Beach

The types of sediment distribution include adding sand along their shorelines, in a mound near the high tide line to be spread out by equipment, and in shallow waters where the waves can naturally move it onto the beach.

Rindge Dam: A Valuable Source of Beach Sand

Studies indicate that much of the of 800,000 cubic yards of trapped sediment behind the dam is suitable for beach nourishment. Photo Credit: Bernard Yin

One of LA County’s largest inland sources of beach-quality sand is potentially behind Rindge Dam. Just three miles inland from Malibu where coastal erosion is currently occurring lies approximately 800,000 cubic yards of trapped sediment (enough sand, cobbles, and rock to fill the Rose Bowl) that should have naturally replenished the coast. Studies show that much of the sand is suitable for beach nourishment. “Los Angeles County is leading the way to protect our coastline using innovative strategies that address multiple challenges at once. This kind of integrated thinking-- like reducing sediment in reservoirs—can also protect our communities from sea level rise and help build a stronger, more resilient future. When we act urgently, we make sure our coast remains open to everyone for years to come,” said LA County Supervisor Lindsey P. Horvath, who represents Malibu in the Third District.

By proactively managing sand resources, LACDBH aims to keep public beaches healthy, resilient, and accessible for generations to come. Through science-based initiatives like SCOUP, Los Angeles County is investing in a future where our coastlines remain resilient against erosion and rising seas.

Restoring Nature’s Flow

Sediment flows from rivers nourishes and shapes beaches, surf breaks, and marine habitats in Southern California. Read how Malibu Creek delivers not just water but also much needed sediment to Santa Monica Bay’s beaches.

For centuries, Malibu Creek has carried the sand that builds our shores and protects our coast. But for 100 years, Rindge Dam has blocked that natural flow. The Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project is working to reconnect mountains to the sea, restore healthy beaches, and strengthen our coastal resilience. Photo credit: RJ Van Sant, CA State Parks.

The Sedimental Journey

Stand on any streambank in Southern California after a rainstorm and you will see a river come to life. Not just with the rush of water, but also the torrent of sediment. Southern California rivers and coasts experience continuous movement of sand, gravel, cobble, and even boulders throughout the year. The movement of this sediment depends on the region’s geography, weather, tides, and waves. Quintessential components of Southern California.

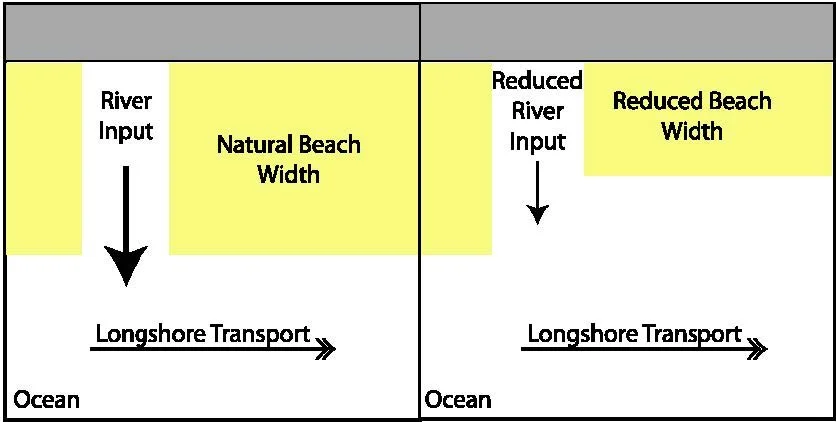

The littoral cells (beach compartments) along Southern California’s coast. Each cell has its own source(s) of sand. Malibu Creek is among the key waterways feeding Santa Monica Bay. Photo credit: Patsch & Griggs, October 2006

The Santa Monica Bay is also known as the Santa Monica Littoral Cell. This name describes the natural forces that act on the coastal mountains and Santa Monica Bay to drive how sediment moves along the coast. Malibu Creek sits at the heart of this system. For Malibu Creek and other streams along the Santa Monica Mountains, material enters the ocean at the estuary. Waves from the predominately from the west push sediment east down the shoreline toward Los Angeles. The coast’s shape changes based on the pace of sediment movement. The westside of the Santa Moncia Bay typically has narrower beaches indicating faster sediment movement. Farther east, near Pacific Palisades and beyond, beaches widen as sand slows. These differences in beach width reveal how geography shapes the rhythm of our coastal system.

Replenishing Our Beaches

Malibu Creek plays a key role in feeding sediment to the bay. Studies show its outflow is one of the bay’s main sediment sources. During storms, Malibu creek sends a pulse of material to Santa Monica Bay. These sediments influence nearshore conditions and sculpt the seafloor. They shape the underwater landscape, build iconic surf breaks, and provide habitat for native marine life. Malibu Creek connects mountains to the bay. But not completely.

For one hundred years, Rindge Dam has disrupted the movement of sediment. Locked behind Rindge Dam is decades of coast. Removing Rindge Dam will restore a more natural flow of sediment to Santa Monica Bay. Dams along with channelization, river course simplification, and coastal armoring have reduced what our local rivers once supplied.

Today, most beach sand comes from artificial nourishment projects. These efforts have added millions of cubic meters of sand. This human input keeps beaches wide, usable, and mostly stable year-round. The Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project will prioritize beneficial reuse of the sediment locked behind Rindge Dam. More importantly we will allow nature, once again, to move sand and gravel from mountains to sea. Restoring this flow is essential for healthy beaches, thriving ecosystems, and a resilient Southern California coast.

Beach sand moves on and offshore seasonally in response to changing wave energy, and also moves alongshore, driven by waves. Dams such as Rindge Dam traps the sediment and disrupts the natural flow of sediment to the beach.

Photo credit: Patsch & Griggs, October 2006

A Dynamic Range

About 5 million years ago, compressive forces folded and faulted the land, uplifting the Santa Monica Mountains out of the sea! Learn about the mountains’ dynamic geology.

Many of the Santa Monica Mountains rock formations were created underwater. Learn about each formation here. Photos courtesy of Malibu Creek State Parks docents.

Imagine standing on the bank of Malibu Creek around 10 million years ago. There would be no Santa Monica Mountains surrounding you! The creek is thought to have flowed in its present course long before the range existed. The sedimentary layers you now see along the ridgelines were once underwater. About 5 million years ago compressive forces folded and faulted the land, uplifting it out of the sea. Its east-west formation is known as a Transverse Range, which is characteristic of Southern California. Transverse Ranges are caused by a bend in the San Andreas Fault which shifts the mountain ranges east-west instead of a north – south direction.

The Santa Monica Mountains is a complex and dynamic range that includes active fault lines, fossils, remnants of volcanoes, and many formations created underwater. The distinctive black-gray and reddish volcanic rocks you see throughout the watershed are known as the Conejo Volcanics. They date back to around 13 million years ago and form the backbone of the range.

The range’s sediment yields susceptible to high erosion rates are attributed to its Mediterranean climate, topography, vegetation, and soil structure. Erosion of the volcanic and sedimentary rocks are carried by flowing water, filling valleys and streambeds with alluvial soil. Malibu Creek offers a transport system that carries sediment downstream to the coastline, providing beach sand for the recreation that Malibu is known for worldwide.

For over a century, much of the Malibu Creek watershed’s high sediment yield has been trapped behind Rindge Dam. Just after the dam’s spillway was completed in 1926, a heavy storm indicated the unanticipated high sedimentation rate that would eventually fill the dam. Although built to store 500 acre-feet of water, by June 1945 the reservoir was down to holding only 76.5 acre feet of water and by 1967 it held less than 15 acre-feet. The abandoned dam now holds approximately 780K cubic yards of sediment (which tends to weigh more than water per cubic foot).

Since September 2024, the MCERP Geotech Team has been sampling, analyzing, and assessing the trapped soils taken from several depths behind the dam. Characterizing the grain sizes and other important material properties is a key component of the pre-construction, engineering and design phase; this data will establish the ecological and hydrological blueprint for restoring the watershed’s natural transport system of delivering much needed sediment to the beaches.

Malibu — The Mecca of Modern Surfing

Malibu is considered “the exact spot on earth where ancient surfing became modern surfing,” according to Paul Gross, a former editor of Surfer Magazine. Here’s why.

Known to the Chumash people as humaliwu, with an unsubstantiated translation to “where the surf sounds loudly,” Malibu Point has been identified by its legendary waves throughout history. Famous waterman Duke Kahanamoku visited his friend, actor Ronald Colman, at the Malibu Colony and first rode the waves there in 1927.

Malibu surf break

Malibu’s naturally formed sandy beach along with the cobble and sand deposits from Malibu Creek in the nearshore, nearshore sandbars, and underwater rocky reefs all contribute to its notoriety as being “the exact spot on earth where ancient surfing became modern surfing,” according to Paul Gross, a former editor of Surfer Magazine. In 2018, this recognition became formal by the State of California Natural Resource Agency designating Malibu Point as the Malibu Historic District.

This cultural and recreational district, part of which is overseen by California State Parks, includes Malibu’s First Point, Second Point, and Third Point surf breaks; the intertidal zone between them and Malibu Lagoon and Surfriders beaches; and the beaches themselves. The Historic District also includes Malibu Pier and Malibu Lagoon.

For surfers, Third Point’s distance from shore and higher wave height affords longer rides for experienced surfers. Second Point’s bigger, faster, but less predictable waves can be challenging to all but the most‐experienced surfers. First Point’s long, evenly breaking waves are the most forgiving for beginners.

Surfing Malibu 1946 courtesy of University of California Calisphere Library.

While other breaks along the coast such as Rincon (south of Santa Barbara) might be considered equally deserving, Malibu’s warmer temperatures in addition to primo waves attributed to it becoming the first pre-wetsuit surfing community in Southern California (c. 1945-1959). It was a place where experimentation, invention, and social activities significantly molded modern recreational surfing. The area's unique coastal and onshore configuration generated long, consistent, and well-shaped waves that drew early surfers. It was here that new equipment was evaluated, new techniques were introduced, and surf culture evolved.

Riding on Malibu’s long waves provided a surfer with so much time the combination of cross stepping the board and carving up and down the wave face became the identifiable Malibu surfing style of the 1950s. Pacific Ocean storms originating anywhere from Baja California to New Zealand produce most of the waves averaging two to four feet high from late summer to early fall. On rare, locally stormy days, surfers can ride eight-foot swells from Third Point to the pier.

Postcard from the 1960s courtesy of Eric Wienberg Collection: Postcards, 1900-1999 Pepperdine University.

Among the local surfers who literally shaped surfing into a new sport was Joe Quigg who, along with other local designers like Dale Velzy, fabricated noticeably shorter, lighter, more maneuverable fiberglass boards with rockers and rails. Quigg’s best friend asked him to design an even lighter version that his girlfriend could easily transport by herself to Malibu. A notably petite regular from Brentwood who bartered sandwiches for surf lessons, she was known as “Gidget,” a hybrid of “girl” and “midget”. In 1999, Surfer Magazine named Kathy “Gidget” Kohner the seventh-most influential surfer in history, inspiring books, films, TV shows and a surf fashion industry.

Other Malibu-related surfers who made it into the International Surfing Hall of Fame were Bob Simmons and Dale Velzy for their contributions in developing the modern surfboard. Kemp Aaberg, Lance Carson, Miklos (Miki) Dora, and Dewey Weber were inducted for their surfing styles and maneuvers.

Joe Quigg, credited by many as the most influential midcentury board-maker, was among a handful of shapers based in Malibu who pioneered balsa surfboard construction. Photo courtesy John Mazza Historic Surfboard Collection, Pepperdine University Special Collections and University Archives

By the summer of 1956, many of the original surfers who put Malibu on the map were leaving the line up for more secluded spots. Malibu continued to serve as a “living laboratory” where pioneer Southern California surfers gathered, developing and testing high‐performance techniques and board designs unique to the area like the famous “Malibu chip”, the forerunner of the modern lightweight longboard. It, along with a variant known as “the pig,” revolutionized and popularized the sport of surfing from 1955 to 1968.

A surf study to gather data and evaluate the famous break is currently underway as part of the MCERP pre-construction, engineering and design phase. This study will support an understanding of the key processes at Malibu Point and any potential impact from the project. The local surfing community has been called on to help with understanding the historic and current surf conditions.

Dawn Patrol: Sunrise at Malibu

(undated, courtesy of Pepperdine University Special Collection Archives)

Rescue and Recovery of Aquatic Species

As part of statewide efforts to help fire victims and wildlife, post fire recovery included saving aquatic species from extinction. Photo credit: Matthew Benton

The last known population of southern California steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in the Santa Monica Mountains survived the Palisades fires as it swept through Topanga Canyon. But the atmospheric river that was to follow just weeks after the fire brought an equal threat of localized extinction to the species.

The destructive wildfire had stripped the slopes of stabilizing vegetation through the canyon. A heavy downpour could send suffocating amounts of sediment into Topanga Creek which would flush into Topanga Lagoon, creating a death trap for all fish downstream. This enormous flow of ash, sediment and debris flowing into the creek could wipe out the southern steelhead population.

Several agencies formed the rescue team to save southern California steelhead. Photo credit: Matthew Benton

As part of statewide efforts to help fire victims and wildlife recover from the Southern California fires, California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) quickly coordinated a rescue mission of southern steelhead in Topanga Creek before the rains. With the help of teams from the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, California Conservation Corps, Watershed Stewards Program, Cachuma Operation and Maintenance Board, and California State Parks, the crew went fishing in the early morning on January 23.

Working in groups along two miles of the creek equipped with backpack electrofishers (guns that briefly stun the fish for capture), nets and buckets, they successfully caught and removed 271 endangered trout. Most of the netted fish were no bigger than 12 inches in length. The snorkel survey conducted by the RCDSMM in November documented over 500 trout. This effort rescued over 50% of the remaining estimated population.

Rescue team at work in Topanga Creek. Photo credit: Matthew Benton

The 271 captured trout were first relocated to CDFW’s nearby Fillmore Fish Hatchery and then transported to Arroyo Hondo Creek on the Central Coast. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife reported that there’s already about a hundred newly hatched trout after they started to spawn the next generation at the new location. “Topanga Creek was heavily impacted by sediment flows during the storms and any fish remaining were lost. It will take several years and some good rains to restore habitat, but we are hopeful that in a few years we can return the trout to Topanga,” noted Rosi Dagit, Principal Conservation Biologist for the RCDSMM.

“These fish are incredible. They are adapted to drier summers and warmer water temperatures; they have a really complex life where they can either stay in the creek their whole life or go to the ocean and come back,” said CDFW Environmental Program Manager Kyle Evans. “They're a very adaptable, important, iconic species whose success represents a healthy watershed, and healthy watersheds mean better water quality for us all. Protecting this population and their home habitats isn’t just good for the trout, it benefits the Californians of this community and beyond.”

Tidewater goby rescue. Photo courtesy of RCDSMM

Earlier in January, the RCDSMM team, in collaboration with USFWS, Dr. Brenton Spies and others also captured and transferred the federally endangered tidewater gobies from Topanga Lagoon. Despite it being the time of year when the camouflaged-color tiny fish reside under rocks and vegetation, the rescue team caught 760 healthy gobies, well exceeding an anticipated goal of 400 - 500. After being held five months at the Aquarium of the Pacific and Heal the Bay aquariums for several months, the gobies were recently returned back home.

Previous to the Palisades in December 2024, the Franklin Fire caused significant habitat damage in the lower part of Malibu Canyon from Rindge Dam three miles down into Malibu burning critical habitat in Malibu Creek. The RCDSMM Stream Team recently completed longitudinal habitat profile and cross section mapping from Cross Creek Rd to Rindge Dam. Mapping entails pulling a 100-meter tape up the center of the wetted creek and documenting habitat types longitudinally. Also documented were the flood prone width of the creek, substrate and depth. This data will assist the MCERP restoration team with sediment transport modeling efforts. While the mapping team saw no trout, invasive crayfish and carp have rebounded since the Franklin Fire. The fire caused silty sandy sediment deposits throughout the system but the team reports that there is still good habitat remaining.

Watch the Topanga Creek rescue effort in a short video directed by Matthew Benton and edited by Zach Edwards:

Fish for the Future | Rescuing an endangered species following the LA wildfires on Vimeo

How Wildlife Recovers from a Fire Event

Image courtesy of the National Park Service. A current study to establish a baseline and understand the recovery process of the mountain range and its wildlife after wildfires now includes both the Franklin and Palisades fires.

Wild cucumber, a native species of the Santa Monica Mountains, emerging after recent fires.

A month before the Palisades Fire, the Franklin Fire blazed through Malibu Canyon at Rindge Dam on December 9. Nine days later it was contained at 4,037 acres. Wildfires are occurring more frequently and violently and have scorched much of the Santa Monica Mountain range. The 2018 Woolsey Fire remains the largest wildfire in the history of the range burning 97,000 acres. In 2019, State Parks began collaborating in the Woolsey Fire Recovery Project, established by the National Park Service and UCLA, to study the impact of the Woolsey fire and its long-lasting effects on impacted mountain ranges. The National Park Service manages this project to establish a baseline to understand the recovery process in wildfires which now includes both the Franklin and Palisades fires.

Left: NASA’s Operational Land Imagers on Landsat 8 & 9 captured the Frankin Fire burn area, combining shortwave infrared, near infrared, and visible light components of the electromagnetic spectrum that make it easier to identify unburned vegetation (green) and recently burned landscape (dark brown). Right: Rindge Dam post fire.

“Our Mediterranean ecosystem is found in only five places around the world, and losing even a small percentage of this habitat can have a significant impact on local biodiversity,” said Miroslava Munguia Ramos, the current lead of the Woolsey Fire Recovery camera project. As a technician through the Santa Monica Mountains Fund, the official nonprofit partner of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, she works with volunteers to study how fauna rebounds in their burned habitat. The Santa Monica Mountains are part of the California Floristic Province, a global biodiversity hotspot, home to a high concentration of unique plants and animals that are at a high risk of being lost due to habitat loss and degradation.

Native giant wild rye regrowth after recent fire events.

The recovery project team studied images from 60 trail cameras placed in remote regions that captured the transformation of plant growth and the return of animals both big and small from Simi Valley to the Malibu coast where the Woolsey Fire had burned. Rebirth began almost immediately. Cameras captured non-native and native grasses sprouting, covering the gray ground with a beautiful green landscape. Many native trees such as Coast Live Oak and Valley Oak, that appeared to be totally burned, were sprouting new leaves and branches, showing their resilience to fire. Wildflowers returned with the rainy seasons, and sometimes rare ones such as the Fire Poppy.

Malibu Creek State Park by January 2019 following the Woolsey Fire that blazed through the park in November 2018.

Most native plants require months to reestablish themselves post fire compared to nonnative grasses and plants which can establish in just a matter of weeks. This results in a habitat that doesn’t support the natural ecosystem as well as natives do. To counterattack an invasive takeover, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and its partner organization the Santa Monica Mountains Fund’s restoration team took on an extreme gardening effort with 150,000 plants grown in a nursery from native seeds. Led by the park’s restoration ecologist Joseph Algiers, the team established restoration sites to plant native vegetation and help support wildfire recovery. Munguia Ramos said that the average survivorship rate of planted native vegetation is about 60% for shrubs and herbs and 55 to 85% for trees to “helps an area get back on its feet.”

Heal the Bay also studied the impact of the Woolsey Fire on streams, particularly the increase in post fire sediment. They found that fire has a significant detrimental effect on water quality, along with the concentrated brominated flame retardants used to contain and extinguish them. The retardants are toxic and persistent, with long-term effects on water quality, aquatic life, and plant life. After a fire, and particularly after a rain, deep pools in streams will be filled with this sediment. The changes can last for many years until the sediment is pushed out, which only occurs after many large storms. Heal the Bay conducts monthly water quality monitoring at 12 sites throughout the mountains to continue to track water quality, particularly after rains when sediment flow and storm drain run off increase dramatically. (A current impact study on the Palisades Fire burning 23,448 acres is here.

To help in the mountain’s post-fire recovery, hiking on slopes after a fire should be avoided because it accelerates dry ravel (sediment going down a slope primarily by gravity) and erosion, and is generally not safe. Hiking will also damage recovering vegetation. For recreation, find parks and trails not recently impacted by a fire.

Camera images from Woolsey Fire Recovery Project, Courtesy of the National Park Service. Top Row: Pictures at same camera location post Woolsey Fire in 8/19 and again in 4/23. Bottom Row: Pictures at same camera location post fire in 4/21 and in 4/23 after two atmospheric rivers weather conditions.

Rindge Dam vs Mother Nature

Pictures taken just four years after the dam was completed documenting damage. Photo from the California Division of Dam Safety archive.

When Rindge Dam was built during the 1920s, there was no environmental impact report required or even a permit needed. The mindset of that era appeared to be that technology and innovation could control Mother Nature.

Until it couldn’t.

In the historical archives documenting the construction of Rindge Dam, correspondence reveals that the dam never served as hoped for the Rindge ranch. Although May Rindge retained one of the state’s most competent engineering teams of Stanford University geologist graduate Wayne Loel and consultant civil engineer A.M. Strong to design and build Rindge Dam, it was a battle against the elements. Correspondence from the state’s Public Works archive is a telling paper trail associated to the ongoing hurdles the dam faced from its construction in 1924 to its decommission in 1967.

Upon retainment by Rindge, Strong sent a letter to the State’s Public Works Engineering Division dated March 1924 requesting any requirements needed to construct a 100-foot-tall and 120-foot-wide concrete dam that could store over 500 acre-feet of water on Malibu Creek. The response was, “The State does not issue permits for the construction of dams but makes examination of site selected and makes frequent inspection during period of construction.”

Loel’s 1924 drawing plans for the construction of a100-foot tall, 120-foot wide at top and 60-foot wide at streamline concrete barrier planned to store over 500 acre-feet of water on Malibu Creek. Despite being a prominent geologist of the era, he did not anticipate the high sedimentation issues in the watershed. From the California Division of Dam Safety archive.

Within a month of the letter, dam construction was underway and by the end of the year completed. A notch in the natural rock outcrop had been cut during dam construction to act as a spillway, Upon a visit to the dam site the state engineer requested several changes in the dam that included a larger excavated spillway to limit the amount of overflow over the dam itself.

In correspondence with the State dated May 1925, Loel acknowledged the dam was unsafe, but knew Rindge was facing financial trouble with her highway lawsuits. He wrote to the State Engineer Office’s, “You are perfectly aware, of course, that the dam with the spillway in its present condition is absolutely unsafe in case of flood water, since the loose boulder material on the south wall of the spillway is entirely unsupported…. As for myself, I do not like to see the dam stand in an uncompleted condition and it appears to me that the present time, when the company is endeavoring to get insurance, would be an opportune moment to press the matter of the completion of the spillway.”

Rindge Dam before the spillway was completed in 1925. Photos courtesy of the California State Water Board.

The State’s reply was, “Please note that before approval may be given the structure must be provided, first, an adequate spillway as already outlined to you in previous correspondence. Second, we should be furnished with measurements of leakage so that determination may be made as to whether grouting shall be resorted to. Third, Final drawings of the structure as completed should be furnished.”

On behalf of Rindge, Loel responded to the State with an alternative and less expensive spillway plan citing his client’s lawsuit costs. The state insisted on their spillway requirements and ultimately Rindge agreed to perform the work. A State Engineering inter-office memo dated April 4, 1926, notes, “It is probably fortunate that, on our insistence, Mrs. Rindge had this work done, as had the water been allowed to pass over the unprotected rock ridge it would probably have cut away the rock to a point which might danger the right abutment.”

However, the problems continued and in 1928, Loel notified the State he was in a lawsuit with Rindge’s Marblehead Land Company for final payment and the issues remained ongoing with the dam. He wrote, “For this reason I hesitate to ask the company for permission to inspect the structure, but believe such an inspection should be made, not only for the protection of the beach residents below the dam but as protection to myself,” adding, “Incidentally, the foundation rock on which the dam rests is identical with the now famous west abutment of the St. Francis dam*, the red conglomerate being readily soluble in water. We had considerable difficulty in making this water-tight…”

Over the years, the correspondence continued, addressing problems related to high sedimentation rates from the watershed that were clearly not anticipated in the building of the dam. By 1941 the dam came once again under state supervision. The Marblehead Land Company continued to request permission to perform work in hopes of improving water storage and getting the outlet pipes to work adequately. A letter dated June 1945 indicated the dam held only 76.5 acre feet of water. By 1967 it was less than 15 acre-feet of water, and the Rindge family requested it be decommissioned which was granted.

They were done fighting Mother Nature.

Upon request by the Malibu Land Company, Rindge Dam was officially decommissioned by the State’s Division of Dam Safety in 1967.

* William Mulholland's St. Francis Dam catastrophe occurred in 1928. Located ten miles north of Santa Clarita, the dam’s sudden and unexpected collapse killed over 430 people downstream and is considered the worst American civil engineering disaster of that century.

**Photo courtesy of the Wienberg (Eric) Collection of Malibu Matchbooks, Postcards, and Ephemera of the Pepperdine Libraries Special Collections and Archives

Help Monitor Malibu Creek Headwaters to Sea

With the new location, the Community Science Program has 7 locations monitoring Malibu Creek from headwaters to ocean.

With the newly added location at Malibu Lookout Vista Point, there are seven locations in the community science photo monitoring program up and running, ready for data collection! Public support uploading images when visiting the locations will help monitor the ecological transformation of the watershed. The program is part of the MCERP’s removal of Rindge Dam in Malibu Creek State Park.

The monitoring posts are located in key ecological locations along the waterway.

The photo monitoring sites are along the Malibu Creek aquatic corridor where dynamic changes can be observed during the project. Documenting the physical condition of the creek and watershed over time is essential to this landscape-scale restoration effort.

The newest location point is at the Malibu Canyon Lookout vista point and will capture both upstream and downstream views just above the dam. “Public participation in taking and uploading photos at this new location will capture the evolving landscape where changes in instream, floodplain, and upland habitats are taking shape. These shifts will reflect the creek's renewed flow, creating a mosaic of habitats that support diverse plant and animal life,” said Russell Marlow, CalTrout South Coast Regional Manager. CalTrout is California State Parks’ public partner in restoring a key watershed in the Santa Monica Mountains.

The photo monitoring sites along the creek from headwaters to coast are at:

Malibu Creek State Park at the confluence of Malibu Creek and Las Virgenes Creek documenting instream, riparian and groundwater dependent habitats – a year-round water source for wildlife.

Malibu Canyon Lookout vista point to observe river, floodplain, and upland habitat changes.

Malibu Lagoon State Park to capture beneficial ecological changes as we restore a more natural flow of sediment and water from the upper watershed.

Adamson House at the changing nearshore and lagoon mouth conditions.

Malibu Pier - Beach Access Stairs – East & West observing nearshore and coastal processes.

Following the instructions is easy! Since the program was launched in May 2024, participants have uploaded 868 pictures documenting the current ecosystems functions. To learn more about the Community Science program and all locations visit the page here.

The Community Science Program offers educational opportunities for schools and organizations.

The Community Science Program offers educational opportunities for schools and STEM environmental science programs. If you would like more information about guided tours, please email restoremalibucreek@caltrout.org.

Once completed the MCERP will restore creek ecosystem functions in the watershed and increase habitat connectivity. Dam removal will restore access to over 15 miles of stream habitat for the endangered southern California steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), improve climate resiliency, and restore a more natural sediment transport process nourishing our beaches and near shore environment.

The community science monitoring program is funded by Resources Legacy Fund (RLF) supporting efforts to remove defunct dams and the Dorrance Family Foundation focused on improving the quality of life in communities by supporting education and natural resource conservation. To obtain more information on the Community Science Program visit the page here.

Get to Know a Species: Invasives

Crayfish, just one of the many invasives in the creek, produce rampantly and eat native fish eggs.

In Malibu Creek, you’re more likely to see a non-native carp or catfish instead of a native Arroyo chub or goby. While these species might not make a difference in enjoying your outdoor experience, it’s a huge difference for the ecosystem. Carp and catfish, along with bluegill, largemouth bass and even abandoned goldfish are just some of the many invasive species in the Malibu Creek watershed.

Frank Vargas Jr. holding a carp he caught in Malibu Creek. Photo courtesy Debbie Sharpton

These aggressive species thrive because they crowd out indigenous species, eat anything, and have few predators. “They create an imbalance in the ecosystem”, explains Debbie Sharpton, conservation vice president of Fly Fishers International, Southwest Council. She has battled crayfish in the creek since 2010. Crayfish produce rampantly and eat native fish eggs. She’s also witnessed the change in the creek’s native fish populations, “When I first started removing crayfish, Arroyo chub would get in our traps, and we’d release them back into creek, but now we don’t get any at all.”

Black Bullhead are in the catfish family and popular for stocking upstream ponds and lakes. Photo courtesy Debbie Sharpton

Where did the non-natives come from? One source are the upstream communities with constructed ponds and lakes. Many of these water bodies contain bass, sunfish, carp, and other non-native species. During the rainy season, the ponds often flood, flushing water into Malibu Creek and bringing the invasive fish along. Also, over the years, people have used the creek for aquaculture and have dumped live bait into the stream and tracked in mud snails. Bull frogs have also been introduced, preying upon and out competing native frogs and other aquatic and terrestrial species.

The catch and keep Fishing for Conservation program helps remove aggressive nonnatives so southern steelhead will have a better chance for survival in local waters. Photo courtesy of Bernard Yin.

High populations of invasive species are considered harmful enough to be on par with other pollutants like mercury and lead. Under the Clean Water Act, Malibu Creek is listed as polluted with non-native species by state and federal environmental protection agencies. This designation can help acquire funding to reduce populations and restore water quality.

With the growing numbers of invasive fish, Sharpton created a new program, “Fishing for Conservation: Steelhead Recovery in Malibu Creek.” Anglers can get maps, information and parking passes to “catch and keep” non-native fish. The program also helps with collecting data from both organized group and single anglers that can be passed on to scientists working in the watershed. For information about the program, visit MCSP.

The Santa Monica Mountains is one of the largest and most significant examples of a Mediterranean-type ecosystem which is only found in 2.3 percent of the world’s land area. Native fish and amphibian populations are an essential part of the region’s tremendous biodiversity. They are a critical part of the food web and serve as a key indicator to the overall health of the ecosystem. A system that includes humans too.

Courtesy of Hashi Clark

2024 Year in Review

This year, the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project (MCERP) progressed at an exciting pace in the planning, design and engineering of opening up a key aquatic corridor in the Santa Monica Mountains. Here are some of the highlights:

Surveys:

Soil investigations are a key component of this project phase to determine the best methods for sediment distribution.

In late summer after bird breeding season, the Geotech team hit the ground drilling behind Rindge Dam to obtain soil samples at varying depths, up to 100 feet down to the stream bed. The soil characteristics are currently being analyzed for grain size and other important material properties to determine redistribution options for the sediment. Key areas for distribution include the beach, in the near-shore coast, or upland disposal. The soil analysis sampling is scheduled for completion by spring 2025. Read about the full Geotech investigation here https://restoremalibucreek.org/blog-posts/geotech-studies-underway

During the year the project team continued the search for endangered Southern California Steelhead in Malibu Creek to help track the species’ populations and distribution throughout southern California. “These surveys are conducted in the streams where southern California steelhead might travel and are a key restoration component of the MCERP,” said Project Manager and Senior Environmental Scientist R.J. Van Sant. Read what snorkel surveys reveal here https://restoremalibucreek.org/blog-posts/snorkel-surveys-what-stream-hunts-can-reveal

We launched a community science program inviting the public to help us monitor this landscape scale restoration project.

Community Science Program

In May, the MCERP launched a community science program with four of seven sites up and operating to help monitor the transformation of Malibu Creek. The program invites the public to take pictures at strategic monitoring locations and upload them to a database that will help document the changing physical conditions along the aquatic corridor. About 500 images have been captured in different aquatic zones to show the varying conditions during the landscape-scale restoration effort. "These photos will tell an amazing story about new beginnings," said CalTrout Program Manager Russell Marlow, Ventura office. Learn how to participate in the program here https://restoremalibucreek.org/community-science

Our outreach team participated in over 40 events throughout the year to discuss dam removal and connecting wildlife corridors to all ages.

Public Outreach and Education

A key part of the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project’s success is outreach and education on dam removal and the need to reconnect migration corridors for both land and water wildlife. Our outreach team participated in over 40 events throughout the year to discuss the project at conferences, festivals, and community events. We led several youth and educational programs at schools and universities around the region and on location at Malibu Creek State Park. Toddlers to teens learned about aquatic ecosystems and endangered species, biodiversity and fish lifecycles within our local streams. We also led site tours for groups to witness Rindge Dam’s impact on the Malibu Creek watershed and the importance of migration for species’ survival. If you have a group that would like more information about our educational and outreach programs, and tours please email restoremalibucreek@caltrout.org.

Geotech Studies Underway

The geotechnical investigations began in September. What are they doing down there?

Photos courtesy of Moffatt & Nichol Engineering.

In September, the MCERP began conducting geotechnical studies at Rindge Dam in Malibu Creek State Park. The studies are an integral part of the pre-construction, engineering, and design phase of removing Rindge Dam.

These geotechnical investigations will help us better understand the century’s worth of accumulated sediment trapped behind the dam. Because of the narrow canyon and severely limited access, a Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopter was needed to transport special equipment into the work area. Among the supplies air dropped in to conduct the studies were a drill rig, small excavator, front end loader, metal bridge, side-by-side ATV, tools and other supplies. Crews were waiting to accept the gear and begin mobilizing immediately.

Photo courtesy of Moffatt & Nichol Engineering.

Samples have been taken at several locations behind the dam to analyze the grain size of the sediment and saturation levels. They have been collecting samples at varying depths up to 100 feet before reaching the natural stream bed. Characterizing the grain sizes and other important material properties will aid in the design of where the material could be placed once removed, including on the beach, in the near-shore coast, or upland disposal.

For three weeks their workday began at 6 am to make the half-mile trek into the canyon and ended when the sun started to set to hike back out. The hike required wearing waders to cross chest-deep water in several locations.

The samples collected during these field studies will be analyzed by project team geotechnical experts. This data and the assessments will be incorporated into the basis of design reports and plan for removal.

The Challenges in Building Rindge Dam

Design drawing for Rindge Dam by Wayne Loel who was a prominent geologist at that time, working with many petroleum companies in Southern California during the oil boom. (From the California Division of Dam Safety archive.)

In the early part of the 20th century, concrete dam construction became the technological darling of reliable water storage, particularly in drought prone Southern California. Most large dam projects were built with public funding, but Malibu mogul May Rindge took on the challenge of building her own private dam to support her 13,316-acre cattle ranch. The challenges she faced were both geological and financial.

Although the State of California didn’t require permits for dams back then, Rindge retained a prominent engineering team of noted geologist Wayne Loel and civil engineer A.M. Strong to design and construct Rindge Dam. Loel oversaw the planning and construction of the 100-foot tall, 120-foot wide at top and 60-foot wide at streamline concrete barrier that could store over 500 acre-feet of water on Malibu Creek. Within a month of their permit inquiries to the State Engineer in March 1924, dam construction was underway.

An example bill sent by the state to the Malibu Ranch Company for traveling from Sacramento to inspect the dam during construction. (From the California Division of Dam Safety archive.)

Decades before Malibu Canyon Road broke ground in the early 1950s, Rindge’s ranch hands blazed a two-mile road up the rocky canyon from Malibu, hauling in 30,000 sacks of imported, slow-drying cement to the dam site. To help cut costs, dismantled railroad ties from the Rindge rail line were also hauled up and repurposed into the dam’s framing.

The Division of Dam Safety’s archives include letters between the project leads and State Engineers regarding the dam’s design, placement of rails, concrete materials, etc. Inspectors traveled from Sacramento to the dam site during construction and billed Rindge’s Malibu Ranch Company for expenses. They watched the crews make and pour wet cement into the forms from buckets suspended by two cables spanning the narrow canyon. As there are no construction joints in the dam, a continuous-pour method of new concrete over the previous pour was made within 24 hours. They completed the dam by December 1924.

Rindge Dam in February 1925 before the addition of the spillway. (From the California Division of Dam Safety archive.)

The Santa Monica Mountains are young in geological years. This caused problems after the first heavy storm. Loel didn't anticipate the erosion of the marine sedimentary soil. Severe storms in the years after construction quickly created the potential for failure issues within a decade. In addition, before Rindge Dam was completely finished, May Rindge had started to run out of money from years of lawsuits over a coastal highway easement through her property. She eventually lost this lawsuit.

The State of California, becoming concerned with dam safety, required an adequate spillway for Rindge Dam. As the dam began to fill, leakage was noted at the left abutment. Loel responded to the state with an alternative plan on cutting a notch through the bedrock for the spillway feature citing his client’s lawsuit costs. The state insisted on their spillway requirements and ultimately Rindge agreed to perform the work. Later inspections proved the spillway was still insufficient and required concrete reinforcement.

This drawing was submitted by Wayne Loel in 1928 to the state's Division of Dam Safety after years of not responding to their request for the official dam blueprints. (From the California Division of Dam Safety archive.)

Correspondence starting in 1925 in the State’s Division of Engineering archive indicates ongoing requests of Loel to submit the dam’s final plans. Additional letters indicated that H. Hawgood had taken over as the project engineer for the spillway construction with flow control gates at the top. He wrote that he was reluctant to ask Loel for the drawings to assist in the construction. In June 1928, Loel finally responded with only a sketch “from memory” in a letter notifying the State he was in a lawsuit with Rindge’s Malibu Ranch Company for final payment.

During the winter storms of 1925/26, additional improvements to the spillway design were needed. Although a final state inspection of the dam was performed in September 1926, the following May during a heavy storm, the spillway gates didn’t work automatically as intended. An on-site dam keeper was hired to ensure the gates operated when needed. Rindge Dam continued to need repairs and have work done on the dam, spillway and reservoir.

A photo taken in 1930 of the caretaker's house to operate the spillway gates when needed.

Many of the local dams built in that era had failure issues and topping the list was aqueduct engineer William Mulholland's St. Francis Dam catastrophe of 1928. Located ten miles north of Santa Clarita, the dam’s sudden and unexpected collapse killed over 430 people downstream and is considered the worst American civil engineering disaster of that century.

Since the last century, we've gained a better understanding of how development can harm our natural resources and ecosystems. River restoration in Southern California is an important step toward correcting past mistakes that have endangered both public safety and wildlife. While we can remove dams, we cannot reverse the permanent loss of such species as the endangered Southern steelhead.

Get to Know a Species: Belostomatidaes aka Waterbugs

A MALE waterbug with eggs on its back. Photo Courtesy of the National Park Service

A male waterbug with eggs on its back. Photo credit: Tom Schulz, National Park Service

Belostomatidae is a family of freshwater hemipteran insects, known as giant water bugs or toe-biters. Abedus indentatus is our local Southern California species averaging.1.5 inches in size but other species can grow as large as 4.5 inches.

Interesting Facts About Waterbugs:

In a bit of role reversal, the eggs are typically laid on the male's wings! Males keep their babies moist, clean and safe from predators. He carries them until they hatch, which is usually at the end of summer, so now is a likely time to find nymphs in the local streams. Males can’t mate during egg duty, but females are free to!

Giant water bugs dine on a variety of aquatic life, including tadpoles, small fishes, insects, and other arthropods. Some are known to kill prey many times their own size. Grasping victims by “raptorial” front legs, they inject venomous digestive saliva into their victim and suck out the liquefied remains.

Giant water bugs can deliver a painful (though nontoxic) bite between the toes of unsuspecting human feet. This explains one of their common names: toe-biter!

Giant water bugs are known to play dead if removed from water. And, if startled, can emit a smelly fluid from their anus.

One species of giant water bug, Lethocerus indicus, is boiled in saltwater or fried and eaten by diners in South and Southeast Asia as a specialty cuisine.

Aquatic invertebrates such as the Abedus indentatus can tell us a lot about water quality. They often react strongly and predictably to changing water conditions. Monitoring fish and aquatic invertebrates can reveal long term impacts to aquatic systems, whereas traditional water quality measurements might indicate a moment in time, such as after a rainstorm.

Aquatic invertebrates can tell us a lot about long term water quality of a stream. Photo credit: Bernhard Yin

The Rindge Behind the Dam

May Knight Rindge with her children Samuel, family dog, Frederick Jr. and Rhoda Agatha on a local beach circa 1896 before she was widowed. She became known as the “Queen of Malibu” and built Rindge Dam to run her cattle ranch, which was all of Malibu. (Photo courtesy of courtesy of local historian and author Suzanne Guldimann.)

May K. Rindge with her children Samuel, family dog, Frederick Jr. and Rhoda Agatha on a local beach circa 1896. (Photo courtesy of local historian and author Suzanne Guldimann.)

May Knight Rindge was God fearing and that was all she feared. Widowed in 1905 at 41 years old with three young children, Rindge continued to manage what she and her belated husband Frederick owned, which was all of Malibu. In 1892, the couple had bought Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit, a one-time Spanish land grant, and most of the homesteads around it. With a gun holster on her hip, she became known as the Queen of Malibu, allowing no one to encroach on her property, extending 25 miles along the coast north from Las Flores Canyon and 2.5 miles inland.

She hired vaqueros to burn out rustlers and squatters. She hired lawyers to drive out Southern Pacific Railroad (SPR) and the Division of Highways (DOH). She strategically built railroads and dams. Her 15-mile private railroad took advantage of a law stating only one rail system could go through a property. It prevented SPR from building a rail line from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara along the coast. By the early 1920s, when a reliable water supply became essential to sustain her 13K+ acre cattle and agricultural ranch, she built her own private dam.

May Rindge (on the right) with an unidentified companion, crosses her Hueneme, Malibu, Port Los Angles Railway trestle bridge over Malibu Creek shortly after she built the stretch of railroad c. 1905. This same stretch of railroad track was later repurposed to help build Rindge dam. Photo courtesy of local historian and author Suzanne Guldimann.

Rindge hired Wayne Loel, a distinguished geologist and engineer of the time. He oversaw the planning and construction of a dam that could store over 500 acre-feet of water on Malibu Creek. The dam broke ground in March 1924 without a State permit, although the State Engineer periodically sent personnel to check on construction.

Ranch hands blazed a two-mile road up the narrow canyon, hauling in 30,000 sacks of imported, slow-drying cement. They also hauled up rails from her dismantled railroad for repurposing in the dam’s construction. Mixing the sacks of cement with water from the creek and aggregate materials obtained on site, they carefully poured the wet cement into the forms from buckets suspended by two cables spanning Malibu Canyon. There are no construction joints in the dam, requiring a continuous-pour method of new concrete over the previous pour within 24 hours.

Early photos of Rindge Dam: Left, a postcard image of the dam (photo courtesy of the Wienberg (Eric) Collection of Malibu Matchbooks, Postcards, and Ephemera of the Pepperdine Libraries Special Collections and Archives). Center, Rindge Dam before completion of the spillway, 1925. Right, the dam caretaker’s house, 1930 (photos courtesy of the California State Water Board).

At 102 feet tall, Rindge Dam was completed in December 1924 with a storage capacity of 574 acre-feet. Because of Rindge’s cost of the highway lawsuits and conflicts with the original dam engineers, the spillway was delayed in completing (she lost the 18-year highway litigation case; a Supreme Court ruling allowed for the public coastal highway through her property). The spillway with four radial gates and a maximum capacity of 5,000 cubic feet per second was completed in September 1926. The total cost of Rindge Dam with spillway was $152,927 ($2,714,454.25 in today’s dollar.)

The cost of the dam, legal fees as well as owed back taxes created mounting debt for Rindge. By 1926, cash poor but land rich, she was forced to start leasing then eventually subdividing and selling parcels of her ranch. One of her first developments was Malibu Colony on the sands of Malibu, building and renting cottages—and later selling them—to early Hollywood stars such as Bing Crosby, Gloria Swanson, and Mary Pickford.

Within five years, the dam was also having issues. An inspection noted that severe flooding had damaged the soft rock backing the spillway. Accumulating sediment from seasonal flooding was rapidly reducing storage capacity. Heavy flooding was also obstructing the outlets. Even with the outlets cleared, the diminishing storage capacity limited the amount of deliverable water through the irrigation system. By June 1945, the reservoir's storage capacity was less than 80 acre-feet, about 15% of the original capacity.

Upstream view of Rindge Dam and spillway in the 1940s after several wildfires and subsequent erosion of the surrounding hillsides. The dam became heavily silted in. Photo, property of Malibu Adamson House Foundation.

During the Southern California oil boom, Rindge hoped to rebound from her accumulating expenses by finding oil on her property. She only discovered an unusual clay instead, which established the famed Malibu Tile Pottery Company. (The artistic tile is on display at the historic Adamson House adjacent to Malibu Lagoon.) However, her debt continued to grow. When Rindge died in 1941, she had $750 to her name.

The historic Adamson House, originally owned by May Rindge’s daughter, Rhoda Agatha Rindge Adamson, features Malibu tiles (pictured here around doorway and windows, and roof line) from the Malibu Pottery Company and is now part of Malibu Lagoon State Park, open for public tours. Visit https://www.adamsonhouse.org to learn more. (photo courtesy of California State Parks)

After May’s death, the family-owned Malibu Water Company continued to provide irrigation water from the dam to residents engaged in commercial agriculture at the mouth of Malibu Canyon where May once had her fields of fruits and vegetables. By the 1950s, more residential development led to a demand for domestic water that came from wells also owned and operated by the Rindge family.

By 1963, continuing floods had nearly filled Rindge Dam with silt, rock, gravel, and debris, rendering the 8-inch distribution pipe inoperable. Upon request by the Malibu Water Company to Public Utilities Commission in January 1967, the dam was officially decommissioned.

In 1984, Rindge Dam was incorporated into Malibu Creek State Park. As part of the MCERP, the dam’s history as well as the Rindge family legacy is being included in the planned roadside interpretive site at historic Sheriff’s Overlook above the dam. Visitors will be able to view the dam removal, learn about the Malibu Creek watershed and local cultural history, all while taking in the area’s majestic beauty.

Rindge Dam today.

References:

National Register of Historic Places Evaluation of Rindge Dam, Malibu Creek State Park, Los Angeles County, California by Scott Thompson, Simon Herbert, and Matthew A . Sterner

The King and Queen of Malibu by David K. Randall, 2016

Snorkel Surveys: What Stream Explorations Can Reveal

Second in a series of blogs on the science and engineering involved in the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project is snorkel surveys.

Snorkel Survey Team (Left to Right): Steve Williams, Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains (RCDSMM); Luke Benson, RCDSMM; Bernard Yin, Rebecca Ramirez, and RJ Van Sant; California State Parks Project Manager for the MCERP, who provided insight on creek monitoring surveys. (Photos by RCDSMM Stream Team)

The Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains (RCDSMM), a project partner of the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project (MCERP), has been conducting southern California steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) snorkel surveys in Malibu Creek for nearly 20 years. The surveys help track the endangered species’ populations and distribution. They are a key restoration component of the MCERP, said Project Manager and Senior Environmental Scientist R.J. Van Sant. He recently joined a survey to help document baseline conditions for the MCERP.

Stream explorations not only track the presence of southern California steelhead but also other native species and the non-native species which tend to be more aggressive than natives. Other important data collected includes stream pool depth, shelter value, visibility, and instream cover. In addition, small data loggers placed throughout the creek track stream temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen. “These data help monitor and track the quality of the overall habitat. All these conditions impact the survival of southern California steelhead and other native species” explained Van Sant.

Invasive species, such as this school of carp, are throughout the watershed. Programs to remove them will help in the recovery of southern California steelhead to the watershed.

If water levels are safe to perform them, stream surveys are usually conducted monthly between March and November. Malibu Creek’s water level can vary dramatically based on the year’s rainfall. Heavy rainfalls for the past two years have kept the creek flowing with many pools.

In June, the snorkeling crew spent two days conducting surveys in strategic locations along the creek. They spent the first day upstream of Malibu Lagoon (restored by the California State Parks and partners in 2012) and the second day surveying up to the base of Rindge Dam and upstream above it. They snorkel approximately 2 miles of creek over the two days.

View of Rindge Dam from Malibu Creek. (Photos by RCDSMM Stream Team.)

To accurately conduct the survey, teams of two to three snorkelers start downstream and proceed upstream in unison. This method helps to observe as much creek as possible and to avoid double counting any species. Depending on the year and season, underwater visibility can range from ten feet or more to just one foot or less.

The crew found that Malibu Creek was still diverse in depth—ranging from a few inches in some locations to 5-10 feet in others! In deeper areas, they dive down to the bottom to check under rocks, tree roots, and undercut banks. They use flashlights to check in crevices and spot animals at lower depths.

The water level in the creek can dramatically vary from year to year based on how much rain falls. The last two years have kept the creek flowing through summer. During droughts, the creek can dry up in most places except the deep pool areas. (Photos by RCDSMM Stream Team.)

While the team primarily focused on searching for southern California steelhead, they documented any animals spotted, including eggs and juveniles. They recorded what they observed.

“The native species that we documented included southwestern pond turtle, California tree frog, pacific tree frog, lots of tree frog and California toad tadpoles, two-striped garter snake, and arroyo chub,” reported Van Sant. “Non-natives documented included lots of carp and crayfish, a Texas spiny softshell turtle, a bluegill, and largemouth bass.”

Rebecca Ramirez holding a southwestern pond turtle. (Photos by RCDSMM Stream Team.)

Disappointingly, the RCDSMM Stream Team hasn’t seen any southern California steelhead or rainbow trout so far this year in Malibu Creek. The last salmonid believed to be seen by the team was in 2018. It couldn’t be determined if it was anadromous or not. Southern California steelhead were once abundant in Malibu Creek but have suffered due to development, invasive species, and human made barriers. This dynamic species travels throughout watersheds from San Luis Obispo to the Mexican border. With the removal of the 100-foot-tall Rindge Dam on Malibu Creek and remediation of 7-8 barriers upstream of the dam, 15 miles of stream habitat will open for the first time in 100 years for the endangered southern steelhead as well as other species to finally access. In the meantime, the Stream Team will keep on the hunt!

Public Helping to Monitor Malibu Creek

MCERP has launched a new Community Science Program to help monitor creek activity. The first photo post is in Malibu Creek State Park.

Visitors to Malibu Creek State Park are actively contributing strategic photos as part of the MCERP’s new community science program. The program helps monitor the changing conditions of the Malibu Creek watershed throughout the restoration. Participants have uploaded over 120 pictures since the program launch in early May.

“Documenting the physical condition of the creek and watershed over time is essential to this landscape-scale restoration effort,” said Russell Marlow, south coast project manager for California Trout.

The program’s first photo capturing site is in Malibu Creek State Park on Crags Road Trail about .25 mile in from the parking lot trail head. Located above Malibu Creek’s confluence with Las Virgenes Creek, the site is considered a dynamic and critical intersection. Uploaded photos from this location will help document the positive benefits expected downstream.

Two more photo sites are soon to be added along the aquatic corridor, with headwaters starting in east Ventura County and ending at the ocean in Malibu Lagoon. “Public participation in taking and uploading photos in strategic aquatic zones along the corridor is helpful for building a robust data set and monitoring the creek’s transformation,” explains Marlow.

The community science monitoring program is funded by Resources Legacy Fund (RLF) focused on dam removal and river restoration in the American West and the Dorrance Family Foundation dedicated to improving the quality of life in communities by supporting education and natural resource conservation.

Get to Know a Species: The Southern California Steelhead

For centuries, the Southern California steelhead roamed Southern California rivers, creeks and estuaries until a stark decline led to their 1997 classification as a federally endangered species. Photo credit: Mike Wier

Southern California steelhead, a species native to southern California's rivers, creeks, and estuaries, were once prevalent, journeying from the coastal mountains' headwaters to the ocean's kelp forests. This fish was a food source and held cultural significance for local tribes, particularly within the Santa Monica Mountains. The Chumash, sharing over 7,000 years of history with the steelhead, felt a deep kinship with these creatures, underscoring the importance of their preservation.

Covering an extensive range of 11,580 square miles, Southern California steelhead populations extend from the Santa Maria River in San Luis Obispo County down to the Tijuana River at the U.S.-Mexico border. They are the southernmost steelhead population globally. Historical records, including photographs, oral histories, and surveys, reveal that these fish once flourished, particularly within Malibu Creek.

What Happened to Southern Steelhead?

For centuries, the Southern California steelhead roamed Southern California rivers until a stark decline led to their 1997 classification as a federally endangered species. Habitat degradation and the obstruction of their migratory paths have critically hindered their breeding and maturation processes. This environmental impact caused a dramatic reduction in their numbers, plummeting from annual runs in the tens of thousands returning adults to fewer than 500.

The 100-year old Rindge Dam has prevented southern steelhead from migrating Malibu Creek from headwater breeding pools to reaching the ocean. Photo credit: Bernard Yin.

Urban infrastructure and water development since the 1920’s has led to significant alterations to the steelhead's migratory corridors. Particularly with dams and water diversions in areas like Malibu Creek. These barriers have not only fragmented their habitat but also potentially threaten the steelhead's unique genetic makeup. The life cycle of the steelhead trout begins in freshwater, where they can either remain as rainbow trout or migrate to the ocean. Unlike salmon, which spawn once and then die, steelhead are capable of multiple spawning journeys. During their time in the ocean, they can grow larger and stronger to help with these difficult journeys. The distinct size and color differences between rainbow trout and steelhead underscore their unique life strategies.

The Challenges for Survival

In the Malibu Creek watershed, the struggle for survival is evident. Limited habitat connectivity below the dam restricts the full lifecycle of the southern steelhead. Biologists are concerned about the potential loss of ocean-going genetics in local rainbow trout populations. Approximately 15 miles of aquatic habitat upstream from the dam offer a glimmer of hope, with the Malibu Lagoon acting as a vital transitional zone supporting young steelhead's preparation for oceanic life.

Southern steelhead populations are in danger of extinction within the next 25-50 years due to anthropogenic and environmental impacts threatening their recovery.

The rapid decline of Southern steelhead populations in fragmented habitats emphasizes the need for rebuilding the resiliency of this impressive fish. The Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project aims to dismantle these obstacles by totally removing Rindge Dam. We can help Southern steelhead reclaim their historical habitat and take steps to ensure the species' survival. This project not only seeks to restore critical juvenile habitats but also aspires to re-establish Southern steelhead as a keystone species within the Malibu Creek watershed, honoring their remarkable journey and vital ecological role.

Aerial photograph of Malibu Creek’s stream-lagoon-ocean transitional zone. Photo credit: Bernard Yin.

Soil Sleuthing: What Geotechnical Investigations Can Reveal

How do you tackle a watershed-scale restoration project? We’ll be sharing the areas of expertise involved in the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project—removing a 100-year-old, sediment-filled dam and mitigating/removing eight upstream barriers. When completed, a key aquatic corridor will be restored to bring back the watershed’s ecological resiliency and support Southern Steelhead once again.

First in a series of blogs on the science and engineering involved in the Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Project is on Geotechnical Surveys

Joe Goldstein, PE, Senior Engineer at Geosyntec in Los Angeles, California provided insight on an important phase in the planning and engineering of removing Rindge Dam.

What is a Geotechnical Investigation?

A geotechnical investigation involves engineers and geologists evaluating the subsurface conditions of a site. This process occurs when planning construction or infrastructure development. It is crucial for comprehending the geological, hydrological, and soil properties of the site. These properties will play a key role in the planning, design, and eventual deconstruction phases in the removal of Rindge Dam.

How are they done?

In a geotechnical investigation, engineers and geologists use different methods to collect information about the underground condition of the site. These methods include drilling boreholes, gathering soil samples, conducting geophysical surveys, and analyzing already available geological data. The collected data is then used to evaluate factors such as soil stability, bearing capacity, groundwater levels, and potential hazards such as landslides.

Why are they necessary?

The results of a geotechnical investigation play a vital role in guiding the design and construction phases. They ensure that necessary actions are taken to reduce any risks associated with the geological conditions of the site. Recommendations may include implementing slope stabilization measures, installing drainage systems, or employing other engineering solutions customized to the site's individual features. Ultimately, a comprehensive geotechnical investigation serves to minimize uncertainties and enhance the safety and efficiency of the project overall.

In 2002, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducted a feasibility study to determine if Rindge Dam could be removed and would be beneficial to the ecosystem. The study included drilling several borings into the impounded sediment as part of geotechnical investigations. (Reference: Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Study: Appendix D - Geotechnical Engineering. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, November 2020. Pg D3-2.)

What is being investigated for Rindge Dam?